The ranks of the steampunk genre continue to swell. Tor.com is wrapping up it’s third annual Steampunk recognition (Steampunk Week, as compared to 2010’s Steampunk Fortnight and 2009’s Steampunk Month), so I thought I’d take some time to pick on a “steampunk” nit. Actually it’s more of a nit that I have with the use of “punk.”

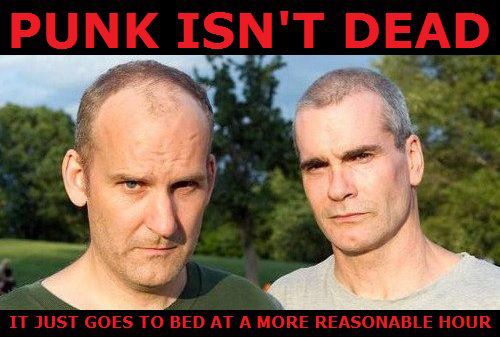

I grew up during the ’80s, when “punk” actually meant something. So it doesn’t surprise me that I find myself amongst the group of people a bit irritated by the over usage of the -punk suffix in SF/F genres. Don’t get me wrong. I love steampunk, but the meaning of punk seems to have been forgotten and diluted.

- 1896 (Algonquian): inferior, worthless, wood used as tinder

- 1904: a worthless person

- 1920: a young hoodlum

It was the “young hoodlum” usage that was copied by the Punk movement in music circa 1974, and by Bruce Bethke in his genre-defining short story “Cyberpunk” in 1980. Bruce Bethke was focused on the criminal element: hoodlums, vandals, troublemakers, delinquents, misguided, disenfranchised youths; in other words: young street punks. In his terms, cyberpunk denoted “the juxtaposition of punk attitudes and high technology.” This was followed by the other canon cyberpunk works (Neuromancer, et al.) which also focused on the same elements.

Based on Bethke’s initial usage, for a work to be truly “punk” the central conflict should revolve around clashing with the status quo. You can see this in Sterling & Gibson’s novel The Difference Engine, in which they set out to write what they call a true steampunk work, rather than a work like Jeter’s Morlock Nights, which I think would be more appropriately classed as gonzo-historical.

Jules Verne’s adventure fiction was the antithesis of the garden party, the Victorian Romance, the popular parlor fiction of the Victorian-era (the fiction of the status quo). People of the Victorian-era “punk” analog would also be people from the bohemian lifestyles: the travelers, artists, poets, and wanderers, such as Michel Ardan in “From the Earth to the Moon.” What’s striking is that this is often the element that modern steampunkers look back to. Look back at the anti-hero Captian Nemo — a wanderer and man without a country — and we see the epitome of the juxtaposition of anti-establishment attitudes and high technology. Verne’s fiction had with much more in common with the youth centered fiction of Mark Twain and Charles Dickens and even the frontier fiction of Fenimore Cooper and Owen Wister.

I’ve seen suggestions for various other “punks” offered up for use: biopunk, bitpunk, dungeonpunk, etc. If a cyberpunk story centers around a world in which computers are accessible to such a degree that kids are using them for acts of low level vandalism, then similarly a biopunk story would be about a world where the biological sciences have reached such a saturation point that even young hoodlums have access to gene altering technology. I wish this were the way that “-punk” was being used and it’s the core of my irritation: “-punk” shouldn’t be synonymous with “genre” (and neither should “opera” for that matter). Unfortunately that has become the common usage of it, in much the same way that the press overuses “gate” when describing scandals (note to future historians: Watergate was a hotel, it wasn’t a scandal about water).

For the record I much prefer the more descriptive term “gonzo-historical” (also coined by Jeter).